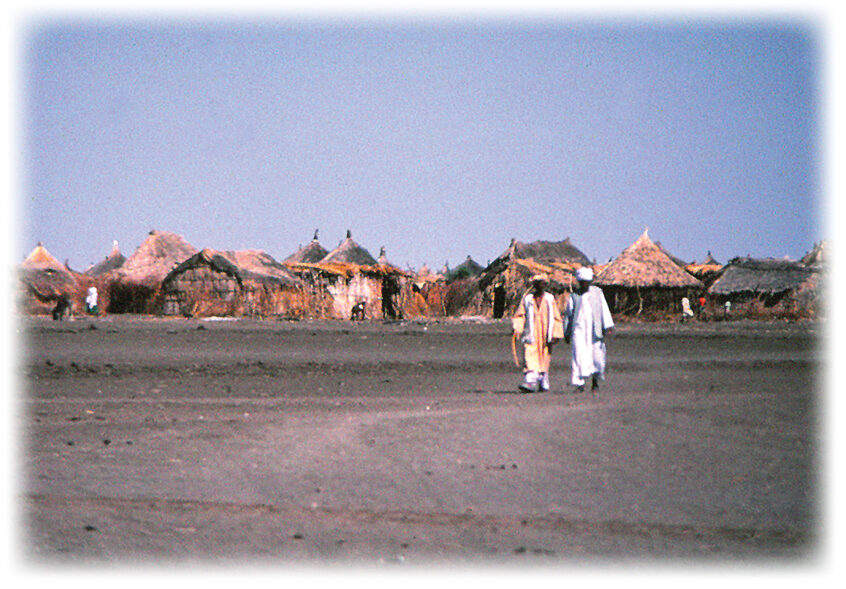

In spite of feeling lonely, fatigued, and scared, I head off into the Somali desert with men I barely know. As we drive west out of Mogadishu the sky is the eternal blue of the end of the hot season before the rains.

Our destination is a refugee camp near Luuq, a town in western Somalia near the border with Ethiopia. Luuq, I’m told, has been in the Guiness Book of World Records (at some point) for having the hottest average daily temperature of any place on the planet. I come from the north and I don’t particularly like heat. I wonder how I will do.

After four hours of driving we leave the paved road. The going becomes slower. We are on a dirt track that looks as though it goes off into nowhere – and it does. There may have been some variation in the land, but, if so, it was too subtle for MY eyes. What if we get lost? Hours go by. At one point the track splits into three. I ask our driver, “Hussein, how do you know which track leads to Luuq?” He responds, “Any of the three will do. They’re all made by UN food trucks and the only place to go out here is to Luuq.”

Finally! We see the settlement looming magically on the horizon like a mirage. On this particular evening there is no electricity. There used to be, but the town’s generator has been broken for months. Darkness near the equator comes suddenly and completely at about 6:00 pm.

Because of the daytime heat, much of the “day” occurs outside after dark. I hear what I cannot see. People walking and talking, children playing, onions frying, the wheels of a donkey cart squeaking, dogs barking. These sounds on a small, local scale mingle with the strange quiet of no traffic, radios, or televisions.

I am in awe. Where AM I? Am I still on the same planet as my loved ones back home? I’m ten hours by car from Mogadishu and two hours from there by plane to Nairobi. But the planes only fly three times a week. So, for example, how far am I really from emergency medical care? To put a telephone call through to the United States from Mogadishu could take days – but at least in Mogadishu the possibility exists. Here it’s impossible.

People sleep in hammocks because at night the heat of the day rises up out of the earth and to be higher means to be cooler. As I climb into my hammock, I consider how I’m out of touch with the world as I know it and as it knows me.

Once settled and gently rocking, I look up. I see stars in the blackest of skies. So many stars! As I gaze, I remember myself as a fourteen-year-old, standing alone on a cold winter night in rural northern Minnesota waiting for the bus to take me to a high school basketball game. While waiting, I stamped my feet to stay warm, looked up into the night sky and picked out all of the constellations I knew. Here, now, in this place called Luuq, thousands of miles from northern Minnesota, where everything is so alien and unfamiliar, I see something familiar: constellations of stars in the rural darkness of a night sky. A sense of safety washes over me.

That moment defined paradox for me. I was as far from ‘safety’ as I had ever been and yet I was safe. And…I had found a way to connect this place that was so unusual to me with a place that was most familiar. I slept.

.

.